The Nostalgia Paradox

Stuck perpetually repurposing the past, are football clubs and brands no longer creating enough original work for us to fondly look back on in the future?

It started with Mad Men.

Specifically, Don Draper’s pitch for the Kodak Carousel, a slide projector that enables the user to curate slideshows of their 35mm memories.

In the scene, his words cut through the room, speaking an essential capital ‘T’ Truth that we all share — a longing for something in the past.

Don Draper opens with the powerful line, “Nostalgia. It’s delicate, but potent.”

In the speech, Don Draper articulates the benefits of the product to his audience, via its ability to establish an emotional connection with the past:

Teddy told me that in greek, nostalgia literally means the pain from an old wound. It’s a twinge in your heart, far more powerful than memory alone. This device isn’t a spaceship, it’s a time machine. It goes backwards, forwards. Takes us to a place where we ache to go again. It’s not called the wheel, it’s called the Carousel. It lets us travel the way, a child travels. Round and round, and back home again, to a place where we know we are loved.

After hearing this all those years ago, nostalgia became an obsession. And it wasn’t just me. The whole world seems infatuated with the past.

But there’s an inherent paradox contained within our relationship with nostalgia that has come to a crescendo. We’re in the peak era of past love.

Original cultural contributions are slowing down. We’re bombarded with the cash-in tactics of rapid repurposing and repackaging the classics.

Unfortunately, this comes in lieu of making bold new things. More classics.

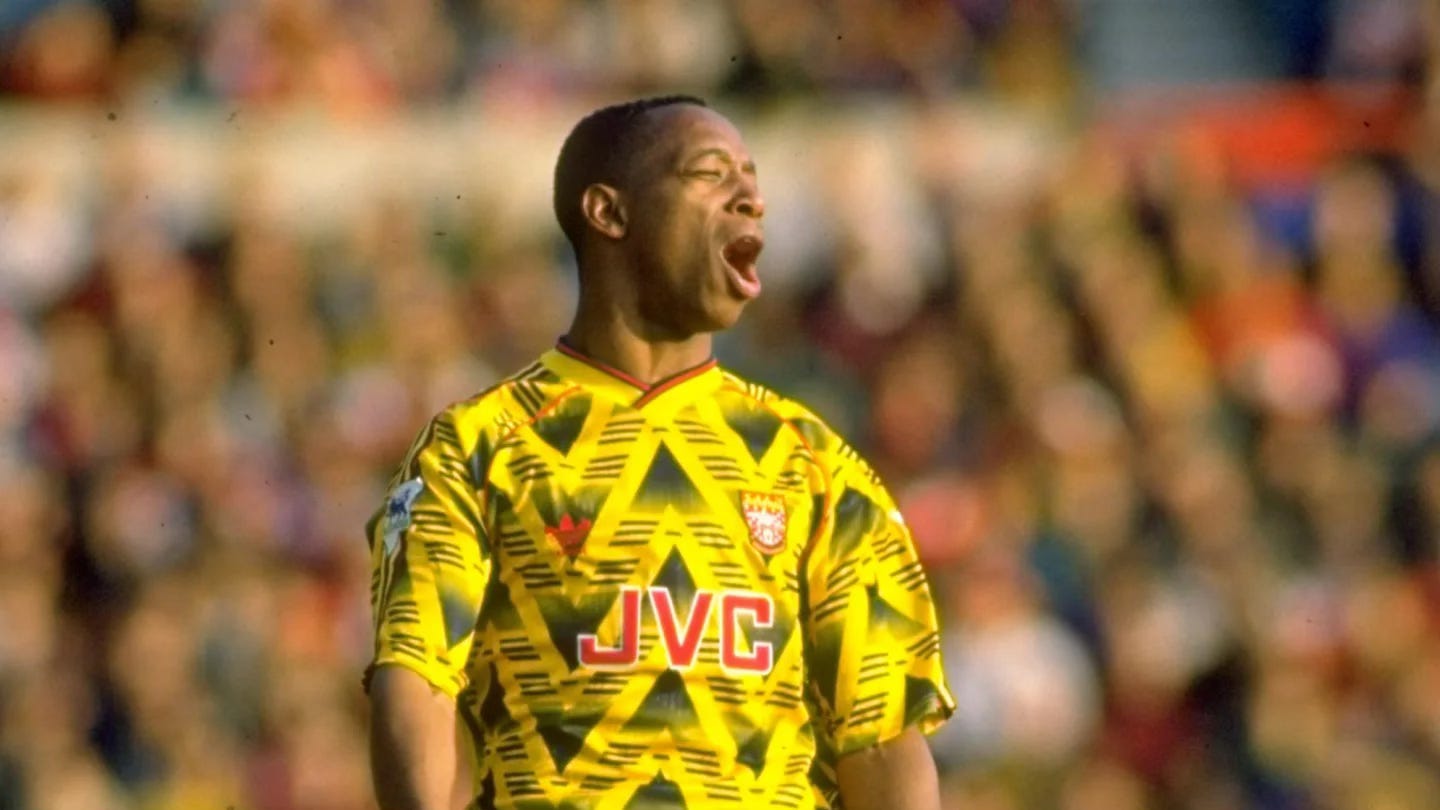

Take Arsenal’s ‘bruised banana’ away shirt of the 91/93 seasons. It’s iconic now. At the time, it split opinions. A garish shirt, that felt distinct from what was happening elsewhere.

Therefore, the shirt ended up on many ‘worst kit’ lists at the time.

Obviously three decades on, the ‘bruised banana’ is now considered a marquee moment in football culture.

And predictably, the shirt has been repackaged and re-released on more than one occasion.

An easy, low-hanging fruit decision. Completely at odds with the groundbreaking nature of the shirt’s initial release.

Nostalgia, so powerful an emotion, has become intoxicating to football clubs and brands. So intoxicating, in fact, that is has anchored football culture into a liminal purgatory-like space and time where originality gives way to shameless and soulless remakes of the past.

It’s not just like-for-like replications of classic kits either.

Every kit, it seems, has to have a story. And in those stories, a display of the club’s history and heritage. Things that have been and gone. Relevant to the future, but not necessary for inclusion in every kit a club releases.

90s kit designs come from an era known for creativity and innovation — Borussia Dortmund’s bright 90s portfolio, Fiorentina’s FILA x Nintendo era, Barcelona’s Kappa range — intent on breaking the mould.

They weren’t bound by the past, but inspired by it to want to build on that legacy, and create one of their own.

Clubs and brands don’t have to take as much of a risky anymore, especially now that they’ve got third shirts to hide behind — a ‘safe space’ to have a bit of experimental fun without risking the resistance of hardcore fans.

The playbook of club’s releasing a safe home shirt, a play-on-the-past away and a boundary-pushing third is now commonplace.

So I can’t help but commend clubs who are willing to break this accepted order.

Chelsea’s home shirt this season has been widely panned. But, just like those defiant shirts from the 90s that refused to be backed into the corner of aesthetic and cultural simulacra, this shirt stands a fighting chance of becoming a classic in time.

Like the person who feels compelled to justify every single line of tattoo ink on their body with a story about late family members or pets, clubs and brands appear desperate to justify that something is objectively ‘good’ because of its links to the past.

Some shirts do this very overtly. Others more abstract. Either way, our ravenous appetite for nostalgia prevents brands from making things that surprise and delight, opting instead to serve an abstract higher purpose. The safe bet anchored in the past.

This is what I call ‘The Nostalgia Paradox’, and it’s pervasive within football.

The Beautiful Game is struggling to come to terms with its place in the world, stuck between a rock and a hard place if that rock is the game’s rich history, and the hard place this new landscape of consumption and engagement.

Clubs use their heritage wrong. Not only that, but they ostracise a whole new generation of young fans in the process of being wedded to the past, making culture feel like something to observe, not participate in creating.

Doing things this way sends a very clear message: the past was great, and the future probably won’t be.

A symptom of something far broader.

But as with every problem, there’s an opportunity attached.

Football clubs must first see themselves as a brand, and then act like one.

An inimitable understanding of a club’s heritage is a prerequisite. Without falling into the trap of replicating it, clubs must work towards re-establishing their values for this shifting landscape.

Nocta’s new Venezia FC range is one rare exception that expertly finds the balance. The designs — from home to away, goalkeeper to warm-up — straddle the dynamic world of Nocta’s streetwear style and Venice’s unique Italian elegance.

These releases are heritage done properly.

Innovation is the only way to disrupt the cycle of replication we find ourselves in, so why aren’t more clubs doing this?

Change isn’t good or bad, it just is. The best always adapt. And therein lies the paradox.

Clubs are so focused on reusing visual elements that evoke feelings of nostalgia right now, that they’re failing to create the next generation of kits that will evoke those same emotions in the future.

So take this as a call-to-action for every football club.

Making history doesn’t mean repeating it.